-

I don’t remember exactly what I was thinking about as I sat on the train from DC, just my bone-weariness and the weight of the stories of the suffering. Leaning back into the headrest, eyes closed, I prayed, or maybe just thought, “Is life on earth just sorrow after sorrow and only that?” The question still hanging in the air, I turned to look out the window just as we crossed the Susquehanna river. The sun was setting on the horizon, and the water caught and reflected back its radiance. The beauty was familiar yet breathtaking. What I saw with my eyes, I knew in my soul as God’s answer.

I’d asked if life on earth was filled with sorrow and sadness only. He spoke before I uttered an amen.

I have been meditating lately on the mystery of the good. That there is still such beauty and joy to be found in this world and in our lives, broken though they may be. For me, the consideration of why this evil? is linked experientially to why this good? It is the flip side of asking about God’s sovereignty in suffering, me recognizing that his ways pertaining to the good and beautiful are just as inscrutable to mortals as his ordaining the bad.

The question first arose as I’d held my newborn son on a hospital bed. Having just walked through a season of grief where I couldn’t perceive God’s reasons for my suffering, I realized I was equally unable to comprehend the scope of his purposes behind the good. I held my son to my chest, pressed my face into his fuzzy head, and wondered, why? Not, “why is there good in this world” in the abstract, but why this blessing? Why for us? For me?

“Because God is good and he gives good gifts,” was the answer Scripture held out for me then, and still does now. No specifics I could grasp, just sufficient reason in who he is and what he wills, leaving me to reverent wonder and grateful praise.

Sometimes, I think in trying to correct the false notion that God is only good when we get the things we want, we can shy away from seeing his goodness through his gifts. I may uphold the truth that God has loving purposes for suffering while failing to see his gracious heart and divine wisdom behind every blessing. It’s true that God is not good because he gives us good things. But the Scriptures teach he gives good gifts because he is a good Father (Mt. 7:11, Ja. 1:17). It may seem obvious, but it is something I need to deliberately meditate on.

I am prone to taking life with all its attendant blessings as a given— givenness not in terms of it being a gift, but as it being an impersonal default. Perhaps this is one reason why gratitude is so important for God’s people, why we are so often exhorted to give thanks. Because we are wont to live as deists, as if God programed the world and left it to run by itself, interrupting only intermittently in the form of the rare miracle or painful trial.

In reality, the only reason the universe does not completely unravel, ceasing to exist this very moment, is because God is upholding it by the word of his power (Heb. 1:3). The truth is the sun rises today on the good and evil because God calls it forth from its chamber as an intentional act of grace (Mt. 5:45). Not a sparrow falls to the ground without his knowledge, which is to say each one is completely within his scope of care (Mt. 10:29). All that happens today, bad and good, he has ordained freely and consciously in his perfect will.

Thus, gratitude for the good things he gives is more than about finding a way to emotionally balance out the hard ones. It is not an adult version of the lollipop after a shot at the doctor’s. To recognize God’s hand behind the good we receive from him is to remove our blinders and see the world as it truly is, filled with his mercy and grace in thousands upon thousands of specific ways. We are recipients of blessings we’d never have thought to ask for, of good gifts we could never have earned even if we’d worked our whole lives for them. Blessings are gifts to be traced back to our loving Father who grants them out of his creativity, faithfulness, and good pleasure. To thank him is to train our hearts to recognize his steadfast love and active involvement in our lives and in the world.

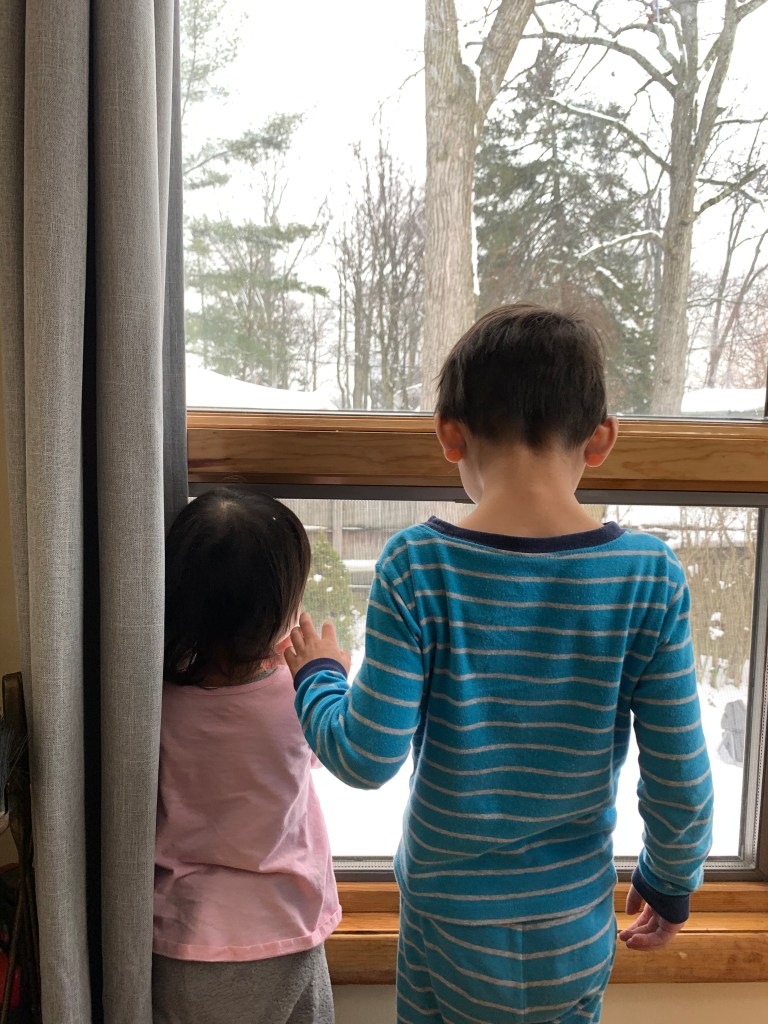

When my children were infants, I was hyperaware of the fragility of their lives, the way their tomorrows were not guaranteed to us. I’d lie down to sleep and, with my head on my pillow, look at them through their crib slats. They were swaddled and so small, and me drifting into unconsciousness meant I had to leave my vigilant-mom post. More than once, my last thought before sleep was the simple request that God allow them to see morning. Each day with them that followed such a prayer felt like a tangible answer from God. A gift, and if I were to probe further into the whys, a mystery.

Really though, today is no different for all of us. Every breath we draw is freely and gladly given by God who sustains our lives by his will and power. We receive our daily bread from his loving hands. And this is just life in its barest form. Even in a world that is groaning for redemption, he fills our days with the good and beautiful— with laughter and open skies, with timely encouragement and faithful words, with work to do and people to love and be loved by.

We put together a last minute escape room for our kids last month, a special birthday celebration for one of our girls. The Chang kids worked impressively as a team, retrieving hidden messages from between piano keys, in a narrow-necked bottle filled with colored water, inside a board game. Jeff and I did pretty well too, I thought, linking clues together for the passcode to a tablet containing messages from aunts and uncles which in turn led to a final “laser” protected clue. The kids loved it, and we loved watching them love it.

What if I walked through life as my kids in that escape room, I wonder, looking out for the intricate ways God has woven goodness and mercy in and through all my days? I have a hunch that I’d be less irritable in the day-to-day, more aware of God’s nearness, patient with those he’s called me to love. In awe of his attentiveness and goodness, might I grow in humility and contentment, abounding in thanksgiving as my prayers slowly conformed to the kinds of petitions described in the epistles (Col. 4:2, Phil. 4:6, Col. 2:7)? Might it even help me to feel more keenly his presence and kindness in the practical graces and consolations he gives in the midst of trials?

What if we were more attune to the ways the good, lovely, admirable, and praiseworthy things in our lives are evidence of his wise and perfect care for us?

Faith in Christ means we hold onto promises regarding the eternal, fixing our gaze on the unseen. But the Holy Spirit also lifts the veil that keeps us from truly seeing the things right before us. As Christians, we recognize the eternal and unseen behind, beneath, and upholding the temporal and earthbound. The good we are given is not meted out by some distant algorithm, but from a Person, in his divine purposes and steadfast love. We know that the Father who did not spare his own son for us is the One who graciously gives us all things (Rom. 8:32). Surely his ways are beyond tracing out. Still, the threads we catch of them here and there inevitably lead us back to him.

I watched the skies the rest of my train ride, grateful for the way God was loving me through rolling clouds and flashes of lightning in the gathering darkness. While I was pouring out my heart to him in the train car, the heavens had been pouring forth speech over me, and God in his kindness had me turn to catch a bit of their message at just the right time. They spoke beauty and glory. They declared that he is God and that there is still good in this world. Even now, they proclaim this. And to their praises, I add my Amen.

-

Doubts are the messengers of the Living One to rouse the honest. They are the first knock at our door of things that are not yet, but have to be, understood. – George MacDonald

He held my hand as we walked through the church lobby. My brave boy had made his way up from the basement, across the church, and to the second floor to tell me about the tornado warning. We were making our way back to the basement when I heard sniffling. “Are you afraid?” He nodded, and I saw his tears. So I held him, and we prayed.

Why did God make tornadoes?, he’d asked me the week before that warning. His question is evidence of his growing understanding of the world and of the Christian claim. At four years old, he is making connections: God made everything. God loves and does what is good. The destruction and death caused by tornadoes are not good. Not knowing how to hold all of that at the same time, he wants to know why? He’s not the only one in our family asking.

For my son, it was tornadoes. For me as of late, it’s been the suffering of beloved, the sinful actions of professing believers, the evil done by man to others who bear the image of God. Why do you allow such things, God? Why do you ordain them? Why haven’t you answered? My why’s rode in on the tail of weariness and persistent discouragement, and an inexplicable sadness that descended on me like clockwork every night.

Why do I believe all this again?

It feels silly, maybe presumptuous as I write it now, but I think I honesty believed I was done with doubt. It isn’t that I’ve ever felt my faith to be particularly strong. Whether because of temperament or experience, I live with a keen awareness of its smallness. Often it feels as if I am just a razor’s edge away from falling into a chasm of unbelief. Sometimes, it’s only when I feel my heart steadied in the congregation— as we worship, recite the Apostle’s creed, take communion — that I realize how shaky it’s been. Even times I feel most certain of what I confess to be true, I know the surety to be a gift for today, not necessarily guaranteed for tomorrow.

In highschool, I grappled intellectually with what seemed to be contradictions between faith and science. In college, the exclusive claim of Jesus among other faiths and the veracity of the Bible. Guilt drove me to questions of my own salvation and an outright declaration to God that I didn’t believe he could love me. For a time doing campus ministry, I just felt a lingering uneasiness about my faith as I fielded questions from skeptics. In the aftermath of miscarriage and as a foster parent, I doubted God’s goodness.

In each instance, God mercifully met me, and in hindsight, doubt was a signal that my faith was being forced to mature in painful but vital ways. Still, I think I’d hoped I’d come out to the other side of it enough times to avoid reliving that rug-pulled-out-from-under-you sensation, the disorienting fog of uncertainty enveloping all that seemed clear just moments before. As I’ve brought my questions to God during this new round of doubt, I’ve seen the anger that drove it, and behind that anger, grief. In this, I’ve found a companion in Job.

I used to plow through the first 37 chapters of Job, the back-and-forth poetry between Job and his friends. I knew the gist of those opening arguments— Job suffered deeply and demanded a counsel with God, his friends blamed him for all that happened to him— and I thought that was all I needed to know before getting to the good part, when God finally shows up. This time, my stomach tensed as I saw Job’s friends grow increasingly angry at him, their charges crescendoing from well-meaning but mistaken to hostile. And when Job spoke, I nodded, underlined, cried, and soaked in his words.

There are many good, helpful answers addressing the problem of pain and evil, but it isn’t my intent to draw them out here, only to say that I felt the mercy of God in giving his people such an account as Job’s. I think of the way people turn on songs and put playlists about heartbreak on replay when they are hurting, and the way we are helped somehow by listening to recording artists expressing our pain with their music. Job gave words to my grief, anger, and perplexity.

At times, dealing with the dissonance of knowing God is in control in the face of evil and pain, it feels like the only two choices put before me are to either reject the Scriptures, or to resort to dealing with suffering as a theoretical construct, as if Job’s children didn’t die, as if his disease-ridden body wasn’t made of flesh and bones. Job disciples me in a different direction though, urging me to go to uncomfortable places beyond a simplistic, unfeeling theology or sinful unbelief.

The complicated reality of life as a believer in a fallen world is that deep despair and great faith can reside in the same person at the same time. Job curses the day he was born, but refuses to curse God. It’s his insistence on the goodness and justice of God that makes his suffering so difficult for him to understand. He holds God responsible for his suffering, yet won’t say God is or does evil. Job won’t stop believing and because of that, he won’t stop asking.

The climax of Job has God establishing his right to do as he chooses. Here, the line is drawn in the sand between doubt and rebellion, questions asked in good faith versus the demand that we be judge and God be accountable to us. Job, having hovered that line, repents for the way he’s crossed it. But it isn’t the theological argument itself that settles things for Job. The resolution is found in his encounter with the One he’d been calling to question. Job exclaims after being forced to reckon with God’s questions for him, “I had heard of you by the hearing of the ear, but now my eye sees you” (Job 42:5.)

This is a great mercy and mystery— how often God’s people have found that on the other side of that “door of things that are not yet, but have to be, understood,” is God himself. So Job is interrogated in a whirwind, and Thomas is invited to touch Jesus’ wounds. The disciples wonder at this kind of man who rules the waves, and the man who prayed “I believe, help my unbelief!” witnesses the healing of his child. It is a pattern in Scripture, God in his kindness revealing himself to those who use what little faith they have to cry out to him. He meets doubters, so that those who had once heard of him, now see him. This is the testimony of my own life, so that doubt, though unsettling, is not quite as scary as it used to be.

Faith, no matter how small, is a gift from God. I know it to be true to my core, the way I have believed in times I thought I’d fall, the way it has been sustained with a supernatural strength not from myself. Sometimes, the questions we hurl in desperation to the sky signify our refusal to let go of the mustard seed of faith entrusted to us, even though we walk weary and broken in this world. Sometimes our whys come because we are holding onto this precious gift in a world where tornadoes exist. So we pray, whisper, and wail the whys as doubt knocks hard on the door. Because there is good reason to hope that God himself will meet us on the other side, and Jesus has promised seed-sized faith will be sufficient until then.

-

And just like that the girls have come to the end of their school year. I know “just like that” is an understatement. But it’s honestly what it feels like. These long months have passed in a blink.

I am grateful. Proud of the ways my daughters have been more resilient than I understood they were being at the time. I think of that morning I saw my brave girl reading at her desk, sitting in the Zoom waiting room for so long I asked her what was going on. Her class hadn’t signed on when she thought they would. She’d been doing so well virtually, I didn’t think to ask until then if it was hard being apart from the rest of her class. She nodded. Then the tears came. Oh, my sweet, tough and tender-hearted girl.

It’s been a tough year, but my kids have flourished and grown, and are healthy and well. There is so much to thank God for.

I also feel a sense of loss for them, more than I’d expected. It started when it finally hit me they’d really come the end of the school year without learning in-person with the amazing teachers they’ve come to love. Jeff felt it too. When he brought them to the school on the last day for ice-cream, he watched our oldest running in the field with her friends. “She got to just be a kid,” he said.

Grief and gratitude. There have been good reasons for both this year. The world is so broken and God is so faithful. Neither truth negates the other, and today my heart is experiencing the interwovenness of both.

It was the same this Sunday, our first day back at church in person after half a year apart. Months ago, Jeff had come home to find me crying. I missed singing with our people so much, longed for the day the worship team wouldn’t be standing in front of an empty sanctuary. Still the joy of gathering again yesterday was mingled with sorrow as I realized how many hard things remain unchanged. Some dated to before the world shut down and some since. There were faces missing— one beloved now worships with the Lord; many other beloved are drifting from the faith.

There is space for both lament and thanksgiving in the Scriptures, and not in a compartmentalized way either, as if they are to be kept for separate places and times. We see it as we read the Old Testament, how at the rebuilding of the temple, some “wept with a loud voice” and others “shouted aloud for joy” so that “the people could not distinguish the sound of the joyful shout from the sound of the people’s weeping” (Ezra 3:13). The legitimate grief of those who’d known the glory of the former temple was expressed alongside of the equally legitimate joy over the new one.

It’s interesting to me that it says both the weeping and joyful shouting were loud. Holding both grief and gratitude is not like mixing cold and hot to get a tepid middle temperature. They don’t balance or cancel each other out. The voices of both were distinct, yet not easily separated. It can often feel that way in life. In the midst of a global pandemic, even more so, I think.

Our lists are long with staggering losses and life-giving graces. There are thousands of reasons to weep. And just as many to give thanks.

So we lament loud. God, we’ve lost so much! There is so much yet to be mended and made whole! How long? Have mercy, come quickly, and make it right!

We praise loud. Lord, for all that has been and is being restored, for all the foretastes of kingdom come, for the grace seen and unseen, we cannot thank you enough!

We will cry and we will shout. We will rejoice and we will mourn. And it’ll be ok if we can’t tell apart the sound of one from the other.

-

Tell me, what is it you plan to do with your one wild and precious life? – Mary Oliver

I saw a dear friend this weekend. Since college, each of us has been witness to God’s firm commitment to keep and lead the other. There’s this different peace about you, she’d said when I first told her about me and Jeff. Later, she stood up front with me at my wedding, and I at hers. Now, the men we married took the kids we’ve had since then out for a hike so we could catch up.

We sat on my deck and talked about how we’ve been wrestling to own the things God has put on our hearts. What it’s looked like for us figuring out life as moms while carrying a specific sense of his calling for work outside the home. Like William Wilberforce, God has put before her a “great object”— a need in the world she has been called to meet as a trailblazer. She has a sharp mind, a passion for justice, a bold faith, and a history of receiving unique opportunities from the Lord. The direction she’s moving in feels obvious to me as her friend, though in this season of life it has taken time for her to walk in it with confidence.

I talked about my own desire, more nebulous than hers, but real nonetheless. She’d known to ask me specifically about it, then told me, “That’s always who you’ve been. It’s almost like, part of the essence of Faith Chang.” I’ve been walking the uneven terrain of self-doubt for a while, and her words were a steadying hand.

It strikes me now how parallel our journeys have been, though hers has her globe-trotting with her family and me rooted in Staten Island for over for a decade. More specifically, in recent years, both of us have had to stop looking to other women for exact models of how our lives ought to look, stop trying to duplicate the obedience of others, however godly those examples may be. In other words, we have needed to learn to discern what it looks like for us to walk in God’s ways.

For years, I’ve had in mind to write a blogpost titled, “That Blogger Doesn’t Know You.” The idea came to me when, as a younger mom, I had to stop reading the flood of Christian articles I’d immersed myself in, mom-blogs especially. Women wrote about how they were led by God to certain convictions about raising kids, serving in their churches, supporting their husbands, and working in the world. The logic of their choices flowed from the Scriptures and made sense to me, so I (often unconsciously) took their standards as my own. The problem was that their choices came out of the way they were called to obey God and though they described one application of God’s truth, their examples were rarely meant to be prescriptive for me. I had to recognize that because I have a different family, am called to a different church, and just am a different person, many of the specific ways I love God and neighbor are necessarily different.

What I’m not saying is that God’s Word is relative, or that it’s okay to excuse disobedience because of our circumstances. Christians don’t just “do you,” following our hearts no matter where they lead. Jesus says we’ll know a tree by its fruit, and Scripture is clear about the kind of fruit a believer ought to show. Following God’s way for our lives can never look like not following his commands. Still, the way we obey his command to love him and neighbor can vary. There are many types of trees that bear good fruit. You do sanctified you.

A few weeks ago, praying with another dear one as she steps through some incredible doors God is swinging wide open for her, I thought of how there is no one else in all of history who has lived or will live her life. Later, I thought about how this is true for every one of us who have ever walked God’s good earth, and well, that took my breath away.

Parents (or aunties and uncles) of a set of siblings know what it’s like, seeing up-close the uniqueness of a child as distinct from his siblings. “She looks like herself,” is what Jeff would say when people asked who our firstborn looked like, but I tried to place her, describe how she was like me or her dad. As she and her siblings grow older though, as I observe differences between them in the questions they bring about God, the way they experience the world, the fears and dreams (literal and figurative) they have, I know their dad is right.

The point of the God-given uniqueness of each individual, that each person in the history of the world is “like himself” or “like herself”, teeters on the incomprehensible to me.

As a kid, I played a computer game that began with the user creating a set of blue, egg-shaped characters. You’d make each one by choosing their hairstyle, eyes, nose, and legs, which was fun until you had to make a lot of them at once. At that point, your best bet was to click on a picture of two dice, the random Zoombini generator. The game only allowed for each character to have one duplicate. Who has enough patience to create 20 computer game characters with four traits each? Not me.

God, though. From the beginning of humanity, through every era, he has fearfully and wonderfully made each of his image bearers, forming every one in his or her mother’s womb. Not only so, but he has determined the times and places for each one of us that we may turn to him. He has not auto-populated human history with the roll of dice. A person’s learning style, height, temperament, tastebuds, and reading pace? Whether or not he’s comfortable in a crowd or she’s always the first to spot the lonely? The things that move you, make you wonder, and catch your breath? These are determined and have been (and are being) shaped by the the Holy Maker of all things and all people.

Moreover, Scripture says that we who are saved by grace are his workmanship. Created in Christ Jesus, God has prepared good works for us to walk into (Eph. 2:8-10). There is such specificity here, how as we go through life, God has wisely set out tasks before for each of us to discover along the way.

Though we imitate the faith of others walking in Jesus’ narrow way, in a very real sense, he is leading us on a road never taken before by any other. And as much as it would be simpler to follow another’s map, more necessary and precious is the promise of his Spirit and guidance, the nearness of our Teacher who speaks to his people, “This is the way, walk in it” (Is. 30:21). What about John?, we may ask. “What is that to you? You must follow me,” replies our Savior (Jn. 21:21-22). So we take one step, then another, though we know not where to.

There is a measure of freedom we experience here, and a sense of fearful trembling too, acknowledging the uniqueness of the one life we alone are called to live before God. He releases us from the crushing yoke of using another’s life as a measuring stick for our own, from trying to live in ways we were never equipped for or expected to live. In some ways though, it can feel harder. It means searching the Scriptures when I’d rather scroll the internet for soundbites of truth. It means I need hard-earned wisdom that can only come through walking daily in the fear of the Lord. It means waiting with patience, seeking his face even more than his guidance, trusting that Jesus meant it when he said his sheep will know his voice (Jn. 10:1-18), believing that even if I get turned around, he won’t leave me behind to fend for myself.

I’ll spend a lifetime learning to walk this way. Seeking to love God with my particular set of desires, talents, limits, sufferings, regrets, preferences, weaknesses, and strengths. Learning to love others as myself—both as much as I love me, and in a way only I can. Being made more like him, and more like me, in my time and place. I expect to be praising God for his wisdom in future years, glad that his course for me turned out to be different than my own vague predictions regarding it. Or maybe, as sometimes happens, I’ll be even more surprised to find that I was right on some counts.

As soon as the husbands and kids returned, my friend’s family had to leave to make it to their dinner plans. The two of us dragged our feet saying bye, even more than the kids did. I hadn’t thought to say it then, but there is a different kind of peace about her, the kind that comes from the Spirit. She is growing into herself, courageously walking the path of obedience that is hers alone to take. We both are, I know. But I see it so clearly in her and it’s beautiful, which gives me hope it might also look that way in me.

-

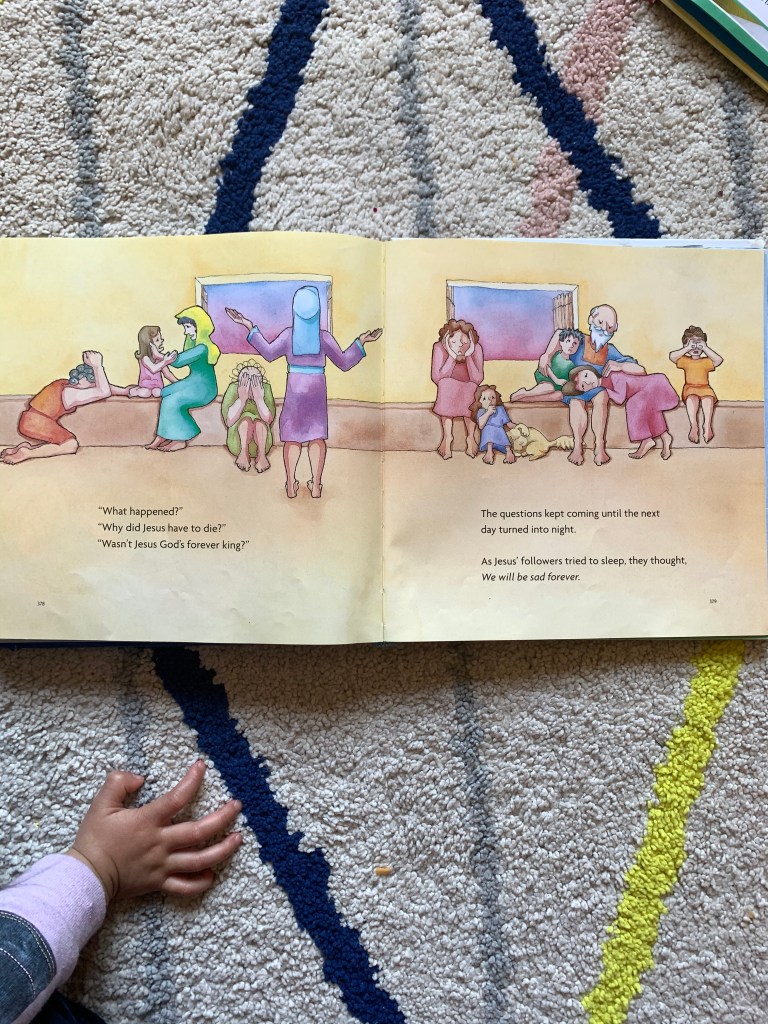

I never thought much about that Saturday, not until I read this page to my daughter. Years later, the phrase, imagined by the author of how the disciples felt that day, would rise to the forefront of my mind as I walked through my own loss:

We will be sad forever.

Today, the Church calendar leads us into remembrance. In between yesterday’s and tomorrow’s services, we embody in real time the hours between the first Good Friday and Easter. He was crucified, died, and was buried, our church recites weekly. That Jesus, God incarnate, died and stayed dead in a borrowed tomb is central to the Christian confession.

On this side of the resurrection, our minds often jump from cross to victory, but the gospel accounts don’t do that. All four writers walk us through Jesus’ burial, and as I read the accounts, I am surprised by how physical, how tangible the descriptions are. Those of us who have seen death up close recognize the details as common— decisions about what to do with Jesus’ body, how and when it would be prepared, where he would be laid to rest. These are the logistics of death. They are mundane. They are utterly and unspeakably awful.

I think of that first Holy Saturday, of the ones who loved Jesus now bereaved and bewildered, reckoning with the fact that they were waking up and Jesus was still dead. How crushing it must have been to lose not only Master and Friend, but their hope. Did they question what all their years with the rabbi had meant, what their proclamations of him being the Son of God amounted to, now that he was gone? “We had hoped that he was the one to redeem Israel,” one follower would say the next day, not knowing he was speaking to the risen Savior himself (Lk. 24:21).

They did not know that as they wept, he lay lifeless for their redemption. They could not understand what was to come.

I see Holy Saturday as the stark contrast between warranted despair and grounded hope. If the disciples had not walked through those horrible days— if Jesus had not really died, and I mean “really” in its being in congruence with the tangible, material, gruesome reality of death in this world — we would remain under the full and just wrath of God (Rom. 5:9-10). And if, lying in the tomb, his heart did not begin to pump and his lungs never drew breath again, if his body did not grow warm and he did not stand to leave his grave clothes behind, truly it would be right to be sad forever. Our faith would be futile, we would be dead in our sins, found to be liars, and of all people most to be pitied (1 Cor. 15:12-19).

As I get older, I find this Saturday increasingly meaningful. Above all, I am reminded that the events we remember this weekend are the basis of any hope we have as believers. As the years go by and life feels more complicated, I am more certain that the simple truth of the crucifixion and resurrection of Christ are worth staking my whole life on. I am increasingly convinced that I have nothing to boast in except the cross of Jesus Christ, and that he who loved me and gave himself for me is worth following. We walk this way between his resurrection and his return, not by sight, but by faith in what God has done and what he has promised he will do.

And as I await my own resurrection, my losses accumulating until then, Holy Saturday is a tangible reminder in the waiting that there is unspeakable joy to come. That God is good and wise even in the most painful trials, and that at the dawning of the new Day, there will be glory beyond imagination for those who put their trust in him.

Easter is coming, but for now we wait.

And beloved, though today we may wait, Easter is coming.

-

I don’t do much cross-posting here, but I have a piece over at Reformed Margins today that may be of help to some readers here. In it I process my absence of tears in response to recent events, and how I believe God is inviting some of us to learn to grieve.

Here’s the introduction:

Why aren’t I angrier? Sadder? Why aren’t I speaking out? Compelled to action for my own people?

Even as fellow Asian Americans have been speaking out in recent days about their grief and anger about the way people in our communities are being and have been treated, I believe there are many of us who are still processing our own disparate responses. Like fellow RM contributor Larry, I have been wondering why my own reaction has as tempered as it’s been to the increasing anti-Asian racism and violence this year.

This week, Larry wrote about the way the model minority myth can numb us to trauma. In his guest post, Peter Ong touched upon the way many Asian Americans deal with the pain and shame of being perpetually othered, “swallowing the bitterness.” Today, I want to explore another reason why some of us, myself included, may be having trouble grieving over anti-Asian American racism. It hit me while reading something Youn Yuh-jung, the 73-year old South Korean actor who starred in the film Minari, said in an interview.

Youn, speaking of the immigrant experience of those in her generation said this: “We expected to be treated poorly, so there was no sorrow.”

You can read the rest of it here: Learning to Grieve Anti-Asian Racism as an Asian American

-

“Go where you wanna go. Do what you wanna do. Believe in yourself.” Sesame Street is playing in the kitchen where my boy has been camping out in front of the HomePod, making requests to Siri. He’s enjoying the music when I hear him think out loud to himself, “Do what you wanna do”? No…you can’t do what you wanna do.

My little guy’s statement, unprompted and so obvious to him, is a bit like the child calling the emperor naked. In our world, self is king and doing “what you wanna do” is the only true way to live. Authenticity is heralded as the supreme measure of what is right. Trust in self a given good. He doesn’t know yet what a counter-cultural sentiment he’s expressing.

My four-year old’s critique isn’t one I am meant to merely rail against “culture” though, it is firstly a reminder for me.

These days, I’ve been sorting through the pull of desires and responsibilities. There are some things I want to be doing, which make the things I ought to be doing feel more onerous than usual. I have been at this— walking with God in my particular spheres of life— long enough to know that I can’t just shirk what I ought to be doing, but the slog of it had been creating a bit of dissonance in me and probably a bit of self-pitiful bitterness too.

I told Jeff yesterday that I wish I didn’t have this other thing I wanted. It was easier to say “yes” to the ought to when I didn’t have desires to do otherwise. I’d rather just not want than say no to what I wanted. To be sure, there are times when God calls us to reevaluate our priorities, to rest, to say no to duties we can no longer shoulder. I am in the middle of such a season. But my more recent struggles aren’t so much a matter of being over capacity as much as the reality that sometimes, I just want to do what I want to do, even as I do what I ought. Which is why some of Jesus’ hard words in the gospels have been actually coming to me as comfort this week.

Working my way through the gospels, I’ve been reminded of how committed Jesus was to giving a realistic view of what it would look like to follow him. He warned his disciples of persecution (Matt. 5:10-12, 10:23; Luke 12:21) and spoke of daily life with him as taking up his cross (Luke 9:23). Loving God will look like hating our own life at times (Luke 14:26). It is so complete a surrender of our own desires and a right to self that Jesus calls it death (Luke 9:24-25).

The force of these verses are not merely their predictive value, but in the promises Jesus holds out. Our death to self precedes our finding true life in him. We die as seeds, forfeiting all we know for the greater glory of a life that bears much fruit (John 12:24-25). These promises are gold. But what I am helped by today is something a bit more peripheral. It is the way that in them, Jesus resets our expectations of life with him.

I’ve always been a bit taken aback by Jesus’ words to the scribe who said to him “Teacher, I will follow you wherever you go.” Instead of affirming his desires, Jesus said to him, “Foxes have holes, and birds of the air have nests, but the Son of Man has nowhere to lay his head.” (Matt. 8:19-22). It always felt a bit harsh to me. Now I’m seeing it as a mercy.

In our first years of marriage, Jeff and I would reflect on how surprised we were at how much we were enjoying it. We had braced for the worst, having been taught since we were teens about marriage— how sanctifying it is to be bound as sinner-saints to another, how it is not easy being exposed and continuing to love in the daily grind of real life. We went in with joy but also a bit of trepidation at the hard work we knew would be entailed in keeping covenant with one another. In hindsight, I probably could have used a more balanced view of marriage, including more of the joys. Still, I’m grateful because I can’t imagine having gone in wearing blinders, how confused I would’ve been had my expectations for it been different.

Jesus knew the scribe had prematurely declared his devotion. Whatever he imagined it’d be like to be a disciple of the Teacher, suffering, homelessness, and scorn needed to be added to the picture. Count the cost of following me, Jesus said in another instance, like a builder of a tower or a king before war. If you aren’t willing to bear your own cross, if you are not ready to be so committed to me that it looks to others like you hate your own life, you cannot be my disciple (Luke 14:25-34).

For those who by grace now follow him, there is a way in which God mercifully sets our expectations so that when things are truly hard, they aren’t compounded by our bewilderment that they are so. “Do not be surprised at the fiery trial when it comes upon you to test you, as though something strange were happening to you,” wrote the apostle (1 Pet. 4:12). Jeff has reminded our church often that the uniform of the Christian is the armor of God, not Hawaiian shorts and a t-shirt. I’ve found that though this isn’t always the case, sometimes what I need most is just that recalibration of my expectations. That image of being dressed for warfare silences my alarm that “something strange is happening” when I don’t feel like life is a vacation.

I’m not exactly sure why it helps me as much as it does, these reminders that the Christian life is costly. Maybe it’s because I’ve come to instinctively take cross-bearing as a given and forget I didn’t walk into this life blind. Perhaps it takes away some of the doubt and guilt I feel when there’s a discrepancy between what I want and ought to do. Or perhaps I’ve just needed the assurance I’m going the right direction, like getting a call from a friend a few miles ahead on a road trip. “It’s a bit winding and you’ll pass by a Chick-fil-a billboard,” they might say, and the sign-holding cows come in view just as you wonder if you’ve lost the way.

Either way, I’m receiving this mercy today, the reminder that if it feels hard to follow Jesus, to obey him and love him, to sacrifice my own desires to know him better, it’s normal. Don’t be alarmed, he’s telling me, if it feels like death. He’s walked this way before, and it’s just as he said it would be.

-

“Can I just have 15 minutes?” is my request, delivered with more edge than I expected. Sometimes, I just don’t want anyone touching me. Which is to say, my body hurts, I’m tired (or busy), and I don’t want anything else asked of me right now.

I think I used to imagine Jesus’ relationship with the crowds like that of a speaker with an audience: They’d listen to him in large numbers like a sold-out stadium, then gather around as people might surround a guest lecturer after a talk. Even with a sizable group, listeners instinctively wait their turn and respectfully give the famous person some breathing space. Being a mom of 4 has changed that perception.

As long as I’m at home, there is no escaping our little crowd. I could be sitting on the mat in front of the stove and somehow it’s now their new favorite hangout. Not only am I no longer alone, the kitchen floor becomes strewn with books and toys. Case in point: Since I wrote that last sentence, a metal bowl has been placed on my left arm and two kids now flank me, holding clementines for me to peel. Another has pointed a large stick in my face.

“Please don’t sit on my arm.”

“I’m not sitting on your arm!”

“Yes, you were. You were JUST sitting on my arm.”

“I’m not sitting on your arm now.”Maybe I used to picture how tired and busy Jesus might be, constantly surrounded by crowds. Now I feel it in my body.

I opened the Scriptures this morning, and I watched Jesus walking by the sea, then making his way up a mountain. He sits down. And that’s when the crowds come.

“The lame, the blind, the crippled, the mute, and many others,” the text says. “And they put them at his feet, and he healed them” (Matt. 15:29-31.)

This week, Jeff served our church in a way he always has. For some reason it caught my attention differently this time. And when I paid notice, my gratitude for my husband swelled. That’s what happened when I saw this crowd surrounding Jesus. I saw my King with fresh eyes.

In an earlier chapter, the moment they recognized him in town, people “sent around to all that region and brought to him all who were sick and implored him that they might only touch the fringe of his garment” (Matt. 14:35-36).

All the sick in the region?

I look across the street at my neighbor’s house and imagine what it’d be like to see homes empty out in Staten Island. If everyone chronically or critically ill went to seek healing all at once at the same place. Who would they bring? Would I go for my back pain? How uncomfortable would it have been to be among those pressing in to touch him? To hear people yelling out for help, their voices so persistent that the disciples would plead with their Master to tell them to stop.

Then I saw Jesus, literally surrounded by the broken.

The lame.

The blind.

The crippled.

“And many others.”I saw him bending down to speak, to listen to a request, to touch, and to be touched.

What kind of Love must this be to not only acquiesce to, but welcome such a crowd? What power would stoop so low? What humility to heal and then, unwilling that the weak would faint on their way home, in compassion prepare a meal for thousands? How tenderly, how kindly, how joyfully he serves. What a sight it was to behold!, even if only in my mind’s eye.

In the future I may remember this scene in the context of motherhood, of Jesus as example to follow, (how do I treat my little flock that, at this very moment, is talking to me about June birthdays, pushing me off the couch, and pulling my hand off the computer keys. “I’m hungry, I’m hungry!” says the arm-tugger.) But right now, I’m just marveling at my King. He is the God of the broken, who welcomes the weak. The God who serves the crowds.

We answered this question after church on Sunday: “What difference would it be make for you to see the church as a hospital for sinners and not as a waiting room for a job interview?” This morning the Lord answered for me: Seeing the sick, I’d behold the Physician among them, and having seen him, my heart would love him so.

-

One of the most formative things my mom did for me growing up was building her library. She never made me read any of her books; I don’t even remember her ever recommending one. It was more of an open buffet of sorts, set out in the living room and made ready for me to serve myself. Through the years, I was nourished at her shelves, more than once helped without anyone other than God knowing just how much.

I think love for reading is more caught than taught. It was certainly that way in my case. We didn’t watch much TV or have video games growing up, so books were naturally a form of entertainment. I read in my free time, during trips in the car, and in the bathroom. On Wednesdays we’d go to the Brooklyn Public Library where the children’s librarian recorded our visits in her ledger. Every third week we signed in, we were invited to walk behind her desk to browse the rolling cart and bring home a reward for our recurrent visits — one free book of our own choosing!

Recently, I helped my parents sort through their books. Most are going to the church library, but I set aside a few boxes for myself. My parents raised us to live simply, you might say frugally, as many Chinese immigrant families do. (I still reuse ziplock bags and buying garbage bags still feels like a scam when plastic supermarket bags work fine.) But my mom has never skimped on books. She says she was taught that by my grandmother, a refugee to Hong Kong and a school principal. It must have been a lesson my mom took to heart, because the shelves in our home were always full.

In highschool, I heard a Christian leader talk about a set of books on her bookshelf she didn’t let others touch. The idea was so foreign to me that it has stuck with me since. In our home, books weren’t meant to be hoarded, they were stewarded with generosity. Guests perused our living room shelves, at times asking about a title, sometimes bringing one or two books home. Years later, when my mom started purchasing books from the bookstore where I now work, she began buying multiple copies whenever there was a good promotion— just in case someone she knew could benefit from a copy. It’s a habit that remains (I joke that the bookstore has a warehouse here in Staten Island) and has been passed on to me, my sister, and my sister-in-law.

Sorting through books at my parents’ place, I consider which titles I’d want my own kids to be able to grab off our shelves on a whim. I remember the time I sat at my bedroom desk, self-consciously searching a systematic theology textbook index. I had checked over my shoulder before finally finding my way to a section on “doubt.”

I set aside a stack of books addressing the questions I had as a teenager, written by authors who have been instrumental in forming my conviction that Christianity is a thinking-religion, able to withstand the challenges of every age.

I pack biographies and stories of revival, books that gave me a vision of Christianity beyond my own experiences. They showed me that the roots of our faith are deeper than current debates and the branches of the kingdom reach to the farthest corners of the earth. Here I was given models to emulate, practical examples of what God is able to do in and through lives of imperfect people given over to his glory.

John Piper has said, “Books don’t change people; paragraphs do, Sometimes even sentences.” I don’t know that I can separate the influence of whole books versus their parts, but it’s true that my most vivid recollections of books are of my mind, heart, even life, pivoting on sentences. Augustine’s defense of God’s incorporeality in Confessions. C.S. Lewis’ defining anxieties as an afflictions, not sins. Elisabeth Elliot’s assurance that our Shepherd wants to lead his sheep more than we want to be led. Jim Cymbala’s stories about a pew collapsing when he first started at Brooklyn Tabernacle Church and his church’s earnest prayers for his prodigal daughter. Andrew Murray’s assertion that we don’t pray because we don’t love– a charge that changed my prayers in college which in turn changed my whole life.

It’s incredible to think of sovereign Love and providence at work here. That God would meet the past, present, and future needs of my heart, mind, and soul through the words and lives of strangers— what a mystery and comfort, what grace and privilege. This is what I’m hoping for as I bring some of these books home and build a library of my own.

Before unpacking the boxes from my parents’ place, I move our bookcases from the second floor down to the living room. Arranging the shelves of our now merged libraries, I think about which ones I want to be eye-level for guests, imagining that after the pandemic, they’ll be able to browse our shelves before and after group gatherings. Perhaps standing there with needs God alone knows, they’ll spontaneously pull out a book and read a pivot point sentence. Perhaps one of the books here will hold out hope for one of my own children during their own darkness of doubt or trial.

Our hand-me-down bookcases now hold some of the same books they did as I grew up. They are an imperfect set, not quite matching and sagging a bit. They are working for us though. Already, my oldest has read through a few books she pulled out on her own: two biographies, a book my brother received on his baptism, a collection of stories about persecuted Christians. I’m going to be the librarian, said my girl as we shelved books.

What matters more the condition of their aged particle board is the invitation these shelves continue to extend. May the weary questioner meet Grace and Truth, may the thirsty and hungry find Water and Bread, and may many be summoned to the Supper through the words served here.

-

Every day you wake up in a world that you didn’t make. Rejoice and be glad.

– Jonathan RogersInstructions for living a life:

Pay attention.

Be astonished.

Tell about it.

– Mary Oliver~~~

The trees invited us to pay attention today.

The kids set out with empty bags; I held my phone for photos and a plant-identifying app. We must have been a sight to behold, how they yelled excitedly and crouched in the middle of the sidewalk, shoving leaves into their Dr. Seuss totes. One man stood in front of his house and just looked at us. At one point I walked straight into my boy who’d suddenly dove between me and the stroller I was pushing. When I turned to help him up, I saw him sitting next to the red-yellow-green leaf he had spotted and gone for. The fiery red ones especially took my breath away, but we got them all, yellows, reds, greens, browns, and every combination of autumn’s colors.

We’d done a walk like this a few weeks ago, but this time, we learned names. So the five of us didn’t just collect “maple” leaves. We collected silver, red, amur, and sugar maple leaves. We didn’t just bring back “oak leaves”— but pin, swamp white, northern red, and scarlet oak leaves. I was so proud when at the end of one walk (we went out twice), my boy, with a full bag, picked up and showed me a leaf he noticed he didn’t have yet.

In the middle of a pandemic and election season in our divided country, leaf hunting might seem like just a nice kid-friendly, socially-distanced activity, a distraction of sorts. In a way it was a good break for me from heeding the beck and call of things that felt urgent, but it was more than that. I was glad when my son showed me his leaf-find, because it meant he was learning to pay attention not just to trees in general, but to each tree we’d stopped under, and to this one in particular. Our naming trees was a kind of noticing, and when we notice in God’s world, we gather kindling for praise.

We returned home, bursting with leaves and worship. I pointed out to them that God could have just filled the world with one generic tree. On that third day of Creation, he could have said “let there be trees” and filled the earth with forests of trees as I draw them– cartoon broccolis that vary only in size, with an occasional circle in the trunk as an owl’s perch. But, praise God, we don’t live in that kind of world. Instead, we emptied the kids’ bags into a box and pulled out green ash, black gum, sweet gum, and honey locust leaves. There were 15 or so species of trees they had gathered from, and these were only the ones with leaves already shed on the sidewalk we walked on. We even had a mystery leaf we’re not sure the app is right about, so the plan is to hunt down the tree again.

What kind of brilliance and creativity must it have taken to fashion all the trees we found within that two-block radius of our house, I wonder. What kind of power must God have to uphold the outermost galaxies and oversee every single tree we encountered today?

Sometimes it’s easy for me to imagine God using his power as brute force, accomplishing great and good purposes, but in an impersonal, blunt way. Knowing God flung planets into space by a simple word fills me a sense of awe at his strength. But studying the differences between types of oak leaves furthers my understanding of his power while offering insight about how he wields it.

Recently, I watched a painting tutorial where the instructor warned beginners not to focus too much time and effort on the first detail they worked on. The reason is that they’d probably get tired and end up with one section they loved that wouldn’t match the rest of the piece. That God doesn’t lose steam— that he is powerful and wise enough to pay attention to the smallest minutiae of creation— honestly stretches my faith. That he uses his strength and mind with precision and creativity in the world offers me comfort and hope. He is big enough to hear my small voice in a broken world (Matt. 6:6-7). He is precise enough to be trusted to handle the details of my life with care (Matt. 6:25-34). And he does not just write my days in a way that is utilitarian, but beautiful (Psalm 136:16).

One of my girls loved pointing out the different reds of the leaves today. I imagine the earth, resting on its axis as on an easel, and God joyfully painting our little corner with the touches of the crimson, pink, and peach that filled her with such delight. Our Creator’s heart must have been so filled with love of beauty as he generously paid attention to every detail of the place he was preparing for us to inhabit. Eden’s trees were not only good for food, but pleasing to the eye. East of the garden, the trees still are his handiwork.

After we labeled our finds, the kids burst out into a spontaneous song about the cherry plum leaf. Today they sang about a tree, but one day the trees themselves will lift their voices. From the cedars of Lebanon to the redwoods of California, the forests will sing for joy when Christ returns. If you listen closely now, you can catch the neighborhood trees rehearsing their doxology.

The earth is the Lord’s and the fullness thereof, the world and those who dwell therein.

– Psalm 24:1 (ESV)Then shall all the trees of the forest sing for joy

before the Lord, for he comes,

for he comes to judge the earth.

– Psalm 96:11-12 (ESV)

-

Subscribe

Subscribed

Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.